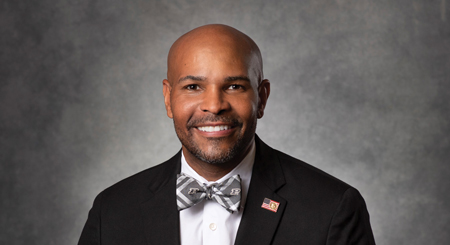

Former U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams, MD, has been heavily influenced in his life by role models. It is in the quotes he recites by heart, from Mark Twain -- “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness” – to Booker T. Washington: “If you want to lift yourself up, lift up someone else.” Now Dr. Adams wants to influence other physicians to get involved.

Dr. Adams is calling on Indiana physicians to step into greater leadership roles as the state and nation navigate a rapidly changing health care landscape.

Adams, who served as Indiana state health commissioner under then-Gov. Mike Pence, delivered the keynote address at the 4th Annual Health Equity Summit and the Association of Surgical Directors Leadership Summit, both held at Purdue University. He urged physicians to look beyond clinical care and engage in shaping the systems and policies that impact public health.

“Physicians are some of the most trusted professionals in the country,” Adams said. “But too often, decisions are made about health care without physicians at the table. We need to lead, not just in the clinic, but in our communities and in policymaking spaces.”

Adams emphasized the importance of advocacy, public trust and community engagement, especially as the country faces growing health disparities and political polarization. He addressed strategies to improve maternal and infant health outcomes, particularly in underserved communities.

Now a distinguished professor and executive director of the Center for Health Equity and Learning (HEAL) at Purdue, Adams continues to champion physician involvement in public policy, with a focus on rural health access and Medicaid reform. HEAL is partnering with health departments across the state — an effort made more urgent by recent budget cuts to public health in the Indiana General Assembly.

Adams, an anesthesiologist, said his own life experiences shaped his commitment to equity and leadership. He grew up in a rural area, the son of two schoolteachers who relied on government assistance. As a child with asthma, he spent extended periods in hospitals and was often confined indoors.

“Despite being in a hospital 23 times in one year, I never met a Black doctor,” he said. “You have to see it to believe you can be it. The hospital was 25 minutes away, and they only had a part-time pediatrician.”

Adams credited his academic interests and limited access to technology with helping to form his path. “We had three TV channels — one of them PBS. I spent a lot of time reading,” he said. “My life may have been different with screens and phones today.”

Mentors also played a significant role in his journey. A study abroad experience in the Netherlands with H.A.W.M. Tiddens, MD, shifted his career goals, and neurosurgeon Ben Carson, MD, was an early influence.

“Maya Angelou said people won’t remember what you did but how you made them feel. I want that to be my legacy,” Adams said. “Ben Carson is very much like that: kind, thoughtful, never raises his voice.”

Adams said organizations like the American Medical Association and the Indiana State Medical Association provided critical access to lawmakers and leadership opportunities. “I went to lobby days and met legislators. I developed a skill set to advance policy,” he said. “That’s where I met Mike Pence and John Wernert, MD, who later recommended me for the state health commissioner role.”

As state health commissioner, Adams said his most significant accomplishment was establishing programs to provide clean syringes to drug users in rural Indiana. Though initially controversial, the programs helped reduce the spread of HIV and have since been adopted in 31 states and Washington, D.C.

As surgeon general, Adams played a prominent role in the national response to the opioid crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and health equity. One of his most notable contributions was his involvement in Operation Warp Speed, the federal effort that helped accelerate COVID vaccine development and, by many estimates, saved millions of lives.

“A lot of physicians tell me they don’t want to get involved in politics,” Adams said. “But health care is inherently political: who gets it, who pays for it, drug policy, abortion. We have to be part of the conversation, even if we stay nonpartisan. Patients lose faith when we become political, but they trust us when we show up to lead.”